Finding Your Author Voice

Fasten your seatbelts, buckaroos! Today we’re talking about voice, which is a slippery eel of a topic if ever there was one, so we’re gonna come at it from a couple different angles and hopefully one of them sticks.

Voice is a hard thing to lock down because it’s entirely subjective. What one person considers strong and fresh might be interpreted by another as weak and derivative.

Here’s the first lesson when tackling voice:

You can’t please everybody, so don’t even try.

With that said, there are certain characteristics which make for good (if not simply unique) voice, and certain stylistic choices you can make in your own writing to heighten the reader’s experience/engagement with your particular brand of wordsmithery.

Okay, so here’s perhaps the single most important characteristic that makes for good voice.

Be Distinctively Consistent

One of the greatest reviews I ever received came from a reader who has consumed practically everything I’ve ever written. It reads as follows:

“I could’ve told you he wrote this even if his name wasn’t on it, it has his writing style all over it…”

This reviewer mentions something simple (which many people will overlook), but to me (the author) confirms I’m doing at least part of my job correctly

What’s that thing?

I’m delivering a consistent story experience. If you pick up one of my stories, you likely have one of three reactions.

- You love it.

- You hate it.

- You’re indifferent to it.

If you love it, fantastic, I recommend you go and grab the other stories. Why? Because I’m stylistically consistent. If you enjoyed (or despised) one of my stories, chances are you’re gonna enjoy (or despise) all the rest.

The point is this: Own your voice.

Make it your strength. Never try and copy somebody else’s voice, that is a sure road to perdition.

Alright, I hear you over there saying, “Yes, Anthony, telling me to own my voice is great, but I came here because I can’t find the damn thing.”

Fair play. Grab a shovel, let’s get digging.

How does one develop their voice?

Remember earlier when I said, “The last thing you want to do is try and copy somebody else’s voice?”

Yeah, I would certainly hope so, it was literally only two paragraphs back…

Okay, so that thing I said was totally true, BUT we need to qualify it. If you set out to write like the next Patrick Rothfuss, you’re gonna fail.

Why?

Because there is only one Patrick Rothfuss. And even if you were somehow to mutate into a Patrick Rothfuss simulacrum capable of churning out buttery smooth prose like the bearded bard himself, it wouldn’t matter, because the world only has room for one Patrick Rothfuss.

This is a two-step process.

First: Read a bunch of stuff from whichever author you’re stalking.

Second: Type out a couple passages from that person’s work.

Step one is easy and obvious, right? How are you supposed to figure out what makes another person’s voice distinctive if you’ve never read anything by said person? That would be, simply put, bonkers.

Don’t be bonkers.

Step two is less obvious. So let me expand. Take one of your favorite passages from one of your all-time favorite authors (somebody who’s work you could easily pick out of a crowd blindfolded) and then what I want you to do is type out that passage into your little computer box thingee.

Parts of your brain light up like a Christmas tree in July when you engage your fingers. Reading is beneficial, sure. But typing out a passage gives you valuable insight into the pace and rhythm of the author you’re studying. Things that you might never notice just by ogling the page.

What sorts of things?

Sentence and Paragraph Structure Length

Short, punchy sentences/paragraphs read quickly. If you want to imbue your work with a sense of breathlessness, contract and condense. Chuck Weng is one of my favorite voice writers and he uses this sort of sentence compactification all the time.

Example from Star Wars: Aftermath

“Chains rattle as they lash the neck of Emperor Palpatine. Ropes follow suit — lassos looping around the statue’s middle. The mad cheers of the crowd as they pull, and pull, and pull. Disappointed groans as the stone fixture refuses to budge. But then someone whips the chains around the back ends of a couple of heavy-gauge speeders, and then engines warble and hum to life — the speeders gun it and again the crowd pulls–

The sound like a giant bone breaking.

A fracture appears at the base of the statue.

More cheering. Yelling. And–

Applause as it comes crashing down.

The head of the statue snaps off, goes rolling and crashing into a fountain. Dark water splashes. The crowd laughs.

And then: The whooping of klaxons. Red lights strobe. Three airspeeders swoop down from the traffic lanes above — Imperial police. Red-and-black helmets. The glow of their lights reflected back in their helmets.There comes no warning. No demand to stand down.”

Notice how Wendig starts with a dense first paragraph. Mostly average length sentences, but the overall complexity of their structures is much higher than what follows when the action escalates. Suddenly we the reader are flung into a lightning quick section where sentences are only a few words each and a paragraph is, at times, comprised by a single line.

That first paragraph is like the slow click-clack of the rollercoaster taking you into the sky, giving you ample time to mull over the drop you’re about to experience. The tension mounts, building up, up, up until finally it’s released in a deluge of fast flying words and paragraphs that drag the reader’s eye down the page wicked fast.

A good exercise when typing out another author’s passages is tweak the sentence structures. Experiment by shortening or lengthening, compressing or expanding their work.

For instance, what happens to Chuck’s passage when we compress that middle section?

“Chains rattle as they lash the neck of Emperor Palpatine. Ropes follow suit — lassos looping around the statue’s middle. The mad cheers of the crowd as they pull, and pull, and pull. Disappointed groans as the stone fixture refuses to budge. But then someone whips the chains around the back ends of a couple of heavy-gauge speeders, and then engines warble and hum to life — the speeders gun it and again the crowd pulls–

The sound like a giant bone breaking. A fracture appears at the base of the statue. More cheering. Yelling. And–

Applause as it comes crashing down. The head of the statue snaps off, goes rolling and crashing into a fountain. Dark water splashes. The crowd laughs.

And then: The whooping of klaxons. Red lights strobe. Three airspeeders swoop down from the traffic lanes above — Imperial police. Red-and-black helmets. The glow of their lights reflected back in their helmets.There comes no warning. No demand to stand down.”

See how much less white space there is in that section. How much slower the middle portion reads? All I did was remove a couple paragraph breaks.

The big take away from this is simple. When talking about voice and style, we are not just talking about what the person says, but rather, how they say it.

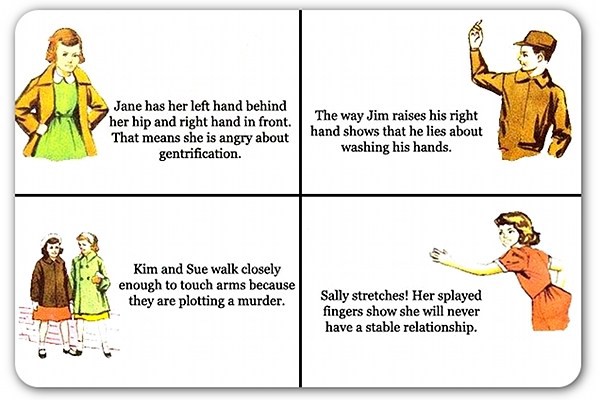

Think of your sentence and paragraph structures as the print equivalent of body language.

W convey vast amounts of information via non-verbal means. How we stand, what we do with our hands, and the expressions we plaster to our faces create context. So it is with how we as writers craft the visual aspect of the page.

The question to ask yourself here is: What’s your preferred sentence/paragraph structure?

For myself, I lean towards average length sentences, though I quite often throw down a very short sentence. Rarely, however, do I hammer out a long (20+) word sentence.

My paragraphs are almost never more than four or five sentences long. Often they are two or three. I’m particularly conscious of this because approaching a huge block of text (especially if you’re reading on a Kindle or other electronic device) is as daunting as going head-to-horned-head with the Minotaur.

Word Choice

Word choice is one of the easiest ways to distinguish your voice, but also one of the most treacherous. Newer writers often have a tendency towards using big, hoity-toity words that sound smart. These are what we call five dollar words. Meaning, in a game of Scrabble, that word would be worth five dollars.

No, wait…actually, that doesn’t make sense. There’s no money involved in Scrabble, is there? I’m not sure what game I’m thinking of, but go with me on this. If Scrabble involved money, then a big word like pulchritudinouswould be worth five dollars, whereas the word pretty would be worth roughly a nickle.

Don’t buy into the belief that big fancy words will somehow make everything better. If you’re trying to find your voice hiding in the pages of a Thesaurus, well, I hate to break it to you, turd-burd: You’re gonna be looking awhile.

Now, that’s not to say you can’t use unique words. For instance, returning to our Chuck Wendig example:

“…and then engines warble and hum to life.”

“…the whooping of klaxons.” “…airspeeders swoop down.”

Words like warble, whoop, and swoop are nothing special in and of themselves, but they clearly (and perfectly) exemplify Wendig’s writing style and voice. Even in the midst of this tense scene of public unrest, he’s throwing in somewhat silly sounding words. Also, notice how beautifully whoop and swoop compliment each other both aesthetically and phonetically. You can bet your ass that was intentional.

Many authors wouldn’t have gone the same route. Perhaps they would’ve chosen words with more implied menace, and that would’ve been fine, within the context of their own voice.

The trick here is to figure out what sort of words you would use. Great exercise builds on what we did earlier, but this time you’re going to rewrite a passage from your favorite author while plugging in different words that fit your unique stylistic sensibilities.

Experiment and Tinker

To get better at writing, you must write. A lot. But at a certain point, just scribbling words on the page won’t level you up. Which is where intentional practice comes in. If you’ve made it this far (god bless your poor, poor soul. I am so sorry), then you’re already searching out those methods of improvement.

Good on ya.

But what else can you do?

Well, remember what we said at the very beginning? The part where I said, “Don’t copy other writers”, and then promptly proceeded to contradict myself in the most fantastic of ways?

Yeah, of course you remember that, it was sort of a pivotal moment in our relationship.

After you’ve spent some time diving into the works of other writers, you need to pick up the pen and start exploring the depths of you. Plum the depths of your creative well.

Preferably in the privacy of your own home.

How do you do that?

By playing outside your comfort zone.

Listen, I love writing first person past tense. It’s my jam. You give me even a slightly interesting character and I’ll find their voice and make it sing. But it took me a long time to figure that out.

I had to write many a story in third person present tense and past tense and future present past tense, to realize where my strengths as an author lived.

Once you locate that strength, however, it’s not enough to simply hammer out the same tune. Your readers will notice and they’ll quickly grow bored of your writing, and rightly so. You need to constantly push and adapt, latching onto the stylistic quirks of your writing that are unique to you and expanding on them.

Push them out of the nest and make them fly.

The take-away is this:

Find your strength, that small nugget of what makes you special, and then leverage the hell out of it.

Use it to grow more unique little nuggets until you have a whole repertoire of nuggets. (A weird analogy. Sorry. I’m getting tired. Losing steam. Forgive me.)

There’s a famous line people use when talking about the derivative nature of all stories. I can’t remember it verbatim, so I’m gonna do you a solid and slap it down on the table here and butcher it for all to see. The gist of it is as follows:

Every story has already been told.

Unfortunately, my special little daisy, this is true (and an important thing to remember whenever somebody tries to sell you the totally awesome idea they dreamt up during their last peyote bender). Ideas are a dime a dozen, all that matters is the execution.

How you tell the story (with your unique voice and style) is what keeps people enraptured.

Now it’s your turn, dearest reader. What sorts of exercises have you done in the elusive quest to find your voice? Get down to the comments and share with the group.

Still unclear (or tangled up on a few of the peculiar analogies I used) get down to the comments and fling some questions at my face. I’m ready for you.